The Reichspogromnacht, also naively called Kristallnacht – The Night of Broken Glass – marks for German Jews the transformation of horror into terror and the beginning of overt and systematic physical violence. Until then, the persecution of Jews generally took the form of coercion and exclusion through racist and segregationist laws. From then on, the physical integrity of the Jewish population was officially threatened, and both the desire and the need for emigration reached a level of desperation: the race out of Germany became an urgent question of survival.

This night symbolizes the end of German Judaism as it was known until then – synagogues are burned, thousands of Jewish men are arrested and taken to concentration camps, their resources for survival are extinguished, their social environment is suppressed. Those who can, due to knowledge or financial possibilities, take refuge in nearby or distant countries, such as Brazil. Those who remain are witnesses to the institutionalization of anti-Semitic ideology.

Tonight, which marks 80 years since that night of terror, makes us reflect on the narrow abyss between staying and leaving, between the power of national identity and the abandonment of family structures, between the perennial human desire for permanence and the imposition of change. As the National Socialist regime forced Jews to live in isolation from German society, there was, in contrast, a reconnection with community identity and the consolidation of Jewish values that had perhaps already been abandoned.

ARI members are today, by birth or ideological legacy, the historical heirs and responsible for remembering November 9th. The ARI exists as a Liberal Congregation in Rio de Janeiro because the National Socialist regime established the laws of discrimination and racism in Germany, and made the terror official with the fateful pogrom (brutal, spontaneous or organized virulent persecution) that night.

An exemplary figure from this period is the Founding Rabbi of ARI, Dr. Henrique Lemle. Like thousands of other Jewish men, Lemle was arrested and deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp the day after the Reichspogromnacht. In her Memoirs, his wife Margot writes that “the project of emigrating to Brazil was already well advanced when, on November 10, 1938, at 7 am, Rabbi Heinrich Lemle was taken by Gestapo men from his apartment at Miquelstrasse 3, 1st floor, to Frankfurt’s Festhalle”, a large meeting building for fairs and festivals, where around 3,000 Jewish men were detained for interrogation and deportation to concentration camps.

The incipient community of German Jews in the Federal Capital of Brazil would have to wait. ARI was the last Jeke congregation (the name given to German Jews) to be founded in Brazil: the first was SIBRA, in Rio Grande do Sul, in 1934, followed by CIP, in São Paulo, in 1936. After the exile of two years in England, Lemle emigrated to Brazil in December 1940 to lead the founding of the Associação Religiosa Israelita, in 1942.

Similar concerns

Between the 11th and 14th of October 1942, the two rabbis of the two nearby liberal German congregations met in São Paulo: from the Congregação Israelita Paulista, Rabbi Dr. Prof. Fritz Pinkuss, and from ARI, Rabbi Dr. Henrique Lemle. The closeness between Lemle and Pinkuss went beyond their exile in Brazil, refugees from the Hitler regime. Both were detained in Buchenwald after the November 9 pogrom and had been students at the Rabbinical Seminary in Breslau, now Wroclaw in Poland. Lemle used, as a source for his 1932 doctoral thesis at the University of Würzburg “Mendelssohn and Tolerance”, an earlier work by Rabbi Dr. Pinkuss from 1929 entitled “The Relation of Mendelssohn to English Philosophy”.

At this meeting, the guidelines for joint operation between the two sister institutions were decided. The third item in the minutes of the meeting states that “on the occasion of November 9th, both Congregations will celebrate this year a special commemorative service on the morning of November 8th. In both Synagogues the manifesto of the two Rabbis will be read. In the coming years, the promotion of these services will also continue.”

It is worth remembering that, in 1942, the war and the National Socialist regime were at their peak. Lemle and Pinkuss, as well as their co-religionists, were aware of the imminent danger and what effect it could have on life in exile, where many did not have full knowledge of the fate of family members who were still in Europe or even of their own fate in the new land. Still in February 1942, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig and his wife Lotte took their own lives in their home in Petrópolis, in a final gesture of hopelessness with the future clouded by the expansion of the Hitler regime and its brutality.

Perhaps for these reasons and now more familiar with Jewish life in Brazil, but accustomed to the organization of the Jewish community in Germany, Lemle and Pinkuss recommend, in item 15 of the minutes of this meeting, “the founding of a federation of Israelite congregations in Brazil in order to satisfy spiritual, cultural, organizational and representational tasks”. In addition to being an unrestricted leader of ARI members, Lemle was a visionary and an important articulator of the full existence of Jews in Brazil.

Bewildered and scared, many tried to return to Germany, trapped between the German and Polish border police.

Polenaktion

The November 9 pogrom has an intrinsic connection with the population of Polish Jews in the territory of the Deutsches Reich, which extended from the Rhine River, in the West, to regions that are today in Polish territory.

At the beginning of the 20th century, thousands of Polish Jews migrated to Germany and Austria in search of a better life, and in the hope of escaping poverty and anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe. In 1938, there were approximately 50,000 Polish Jews in Germany and 20,000 in Austria. After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, the Polish government feared a mass return of its Jewish citizens living abroad and enacted a law affecting the passports of Poles who had lived outside the country for more than five years. Citizens were required to obtain a special endorsement stamp in their passports by October 30, 1938, a Sunday, to keep them valid. The lack of a stamp meant the loss of Polish citizenship and, consequently, the closure of the country›s borders.

As of Thursday, October 27, the German government decreed the deportation of these “stateless” Jews. During this Polenaktion (Operation Poland), 17,000 Polish Jews were detained and deported by train or on foot to the German-Polish border. In many cases, the government deported only men because it believed women and children would find a way to unite with their husbands and fathers. Along the way, many perished from terror or disease; others, in despair, took their own lives. At the border, deportees were forced to hand over all their possessions to the German government, and were allowed to keep only ten Reichsmarks.

Only a first small group was admitted to Poland, the rest were refused by Polish border guards. Bewildered and scared, many tried to return to Germany, trapped between the German and Polish border police. When the Polish government finally allowed them to enter, the Jews were housed in several border towns in a bizarre “no man’s land.” Food and medical care were scarce. Thousands of displaced Jews sought shelter in stables and barns. Jewish organizations in Poland set up refugee camps as the Polish government tried to get Germany to take back the Jews.

In November 1938, Poland granted the stay of Polish Jews. By August 1939, everyone had left the border cities. And on September 1, Germany invaded Poland. Then the Second World War began.

The National Socialist government claimed that the November 9 pogrom was a spontaneous retaliation by the German population, outraged by the murder of a German diplomat in Paris by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Polish Jew living in Paris, who claimed to have acted to protest against the Polenaktion and the deportation of his parents to Poland.

October›s Operation Poland was as significant as November›s firebombs. It can be said that this operation was a precursor to sudden arrests, persecution, deportations, violence and property confiscation.

Judenstempel

In contrast to the year 1937, considered a silent year regarding the virulent persecution of Jews and discreet regarding movements to prepare for war, 1938 was noisy and forceful, especially with regard to German foreign policy resolutions with their neighboring countries. This year, many countries made it clear, whether in agreement with Germany or not, that Jews were not welcome in their territories to transit or go into exile.

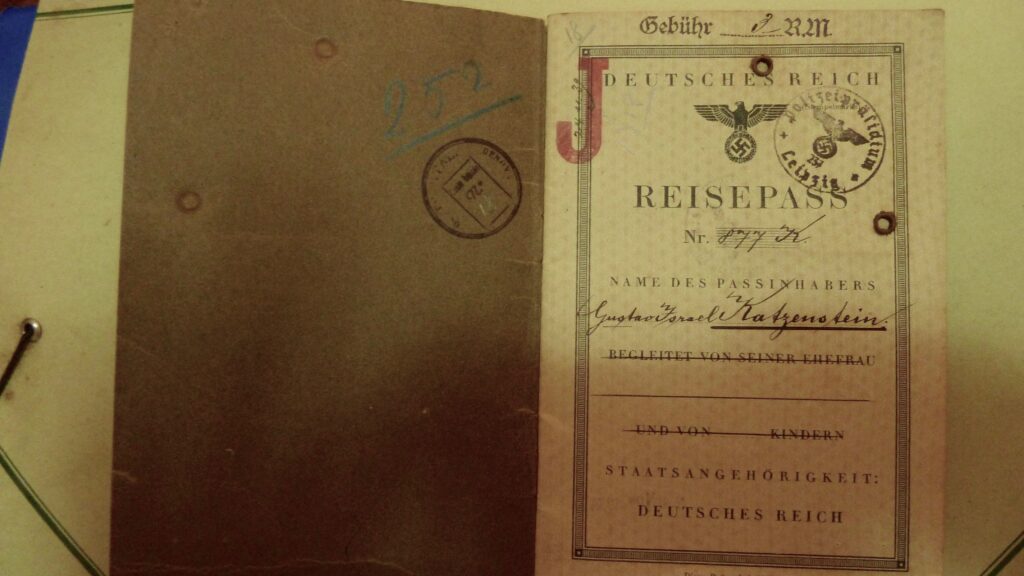

on October 5, 1938, the German government introduced the Judenstempel – a red letter J stamped on German passports that identified the holder as a Jew.

Unlike other European countries, in Germany the secular integration of Jews with the local population and culture and, historically speaking, linguistic proximity were, at different times and for different reasons, a blessing and a curse – Ashkenaz means, in Hebrew, Germany; The Yiddish language was born as a social movement in that region, before the country of Germany even existed.

On August 17, 1938, the German government forced its Jewish citizens to include, in their first names, a stereotypically Jewish name to distinguish them: men had to include Israel and women, Sara.

Later, on October 5, 1938, the German government introduced the Judenstempel – a red letter J stamped on German passports that identified the holder as a Jew. On July 7, 1941, the covers of the passports would also be stamped.

With these measures, German Jews were easily identified at border posts. There are studies that suggest the participation of Swiss authorities in this decision which, given its neutrality and political stability, was privileged as a country of exile or transit. With J, it was up to the receiving country to allow the potential tourist to enter. Switzerland made the entry of German Jews conditional on the issuance of a prior visa by the competent Swiss representation in the country of origin or residence. In addition to German Jews, this measure indirectly affected Poles affected by Polenaktion and other Jews trying to immigrate.

The invention of the Judenstempel was initially attributed to the head of the Swiss border police. However, recent studies attest that the stamp was in fact introduced by mutual agreement between Switzerland and Germany, following a counter-proposal by the German authorities to the requirement, by the Swiss Federal Council, for visas for all its citizens indiscriminately.

In 1938, especially during the Reichspogromnacht, the siege closed. Staying is no longer an alternative, leaving becomes a privilege. Over the next six years, the world will witness one of the greatest crimes of and against humanity. In Rio de Janeiro, the sound of spoons hitting pot lids in Praça Onze on May 8, 1945 will celebrate the end of this nightmare. And ten years later, on May 14, 1948, the world will watch a nation regain sovereignty over its own destiny.